Reasserting Value for Money in a Changing Global Aid Landscape

Delivering more with less through a smarter value lens

Reasserting Value for Money in a Changing Aid Landscape

The world is demanding more from development efforts than ever before. Escalating climate impacts, entrenched poverty, and spreading conflict create unprecedented needs, while progress on global goals falters. Yet, precisely when ambition is most required, resources are shrinking. Major donors are cutting aid budgets, funding faces disruption, and any money spent is under intense scrutiny. This stark reality demands a fundamental shift in how we deliver and demonstrate value with increasingly scarce resources. This isn't just a budget challenge, it's a fundamental call to prove that even scarce resources can deliver profound, lasting impact in the face of overwhelming complexity.

Delivery Associates has partnered with Ripple CoLab to develop a new approach to value for money that meets this challenge head-on: Emergent Value. Moving beyond traditional frameworks that struggle with complex challenges, we've developed a systems-based methodology that identifies powerful leverage points where targeted investments create ripple effects throughout entire programs. By mapping how different elements interact, engaging diverse stakeholders in defining success, and continuously adapting to emerging evidence, our approach enables organizations to achieve dramatically more impact per dollar invested. In an era where every investment faces intensified scrutiny, Emergent Value provides a practical pathway to deliver transformative, sustainable results—even in the most constrained funding environments.

Why VfM Matters Now More Than Ever

In today's development landscape, we face an unprecedented challenge. Global needs are intensifying, climate impacts accelerate, conflict zones expand, and progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals has stalled or reversed. Meanwhile, the resources to address these mounting challenges are diminishing rapidly.

Recent official development assistance (ODA) cuts illustrate this trend starkly. The UK government , is reducing its aid commitment from 0.58% to just 0.3% of national income, the lowest level since 1999. In the US, an unprecedented shake-up at USAID has frozen or terminated the majority of programs, effectively stripping away nearly US$60 billion in funding. Across the donor community, aid budgets are contracting (by 7.1% from 2023 to 2024 according to OECD, with aid flows directed specifically to developing regions already in decline since 2020), precisely when they're needed most.

This widening gap between needs and resources has intensified scrutiny from governments, funding partners, and taxpayers. Every dollar must stretch further, and funding decisions face unprecedented examination. For donor agencies, implementing partners, and governments alike, the imperative is clear: we must not only achieve more impact with less money, but also prove that scarce resources are being put to the best possible use.

We see this as a call to action, one that requires reasserting the importance of “value for money” – not as a buzzword or box-ticking exercise, but as a critical lens to make hard choices and prove that shrinking budgets can still achieve meaningful results in challenging and complex contexts.

The Limitations of Traditional VfM Approaches

Conventional approaches to defining value for money, often encapsulated by the '3Es' (Economy, Efficiency, Effectiveness) or expanded to include Equity and sometimes Cost-Effectiveness (the '4Es' or '5Es'), provide a foundational language and structure for assessing the use of public funds. These frameworks emphasize minimizing the cost of inputs (Economy), maximizing the outputs achieved for a given level of input (Efficiency), ensuring the outputs lead to desired outcomes (Effectiveness), and considering the distribution of benefits (Equity). For projects with clear inputs, activities, outputs, and predictable outcomes – such as infrastructure construction or the delivery of specific commodities – these frameworks offer a useful, structured way to track progress and ensure accountability.

Despite their utility, traditional value for money frameworks exhibit significant limitations when applied to complex development challenges, particularly those involving systems change.

These conventional frameworks fall short when confronting today's complex development challenges:

- Tunnel Vision on Tangibles: Traditional value for money tends to fixate on easily measurable outputs (e.g. number of wells drilled or textbooks delivered) and short-term cost-efficiency. This can undervalue less tangible outcomes like improved institutional capacity, behavioral changes, or stronger community trust – changes that are crucial for sustainable impact but hard to quantify upfront.

- Linear Assumptions: Classic value for money analysis often assumes a linear cause-and-effect: you spend X to get Y result. In complex programs, results are non-linear – multiple interventions interact, and change happens through feedback loops. Traditional frameworks offer little guidance on evaluating multi-faceted efforts where, say, improving healthcare might also involve education, infrastructure, and policy changes working together. They don’t handle synergies or ripple effects well, nor do they account for the time it takes for systemic reforms to pay off.

- Static Snapshots: A conventional value for money assessment is usually a one-time or periodic calculation, not a living process. This static view fails to account for how value can evolve over time. In a reform initiative, what looks less “efficient” in the short run (e.g. spending extra time on coalition-building) may yield huge dividends later. Traditional approaches can therefore bias against the very strategies – like stakeholder engagement or adaptive trial-and-error – that enable long-term success.

- Narrow Stakeholder Perspective: Lastly, old-school value for money doesn’t always incorporate who defines “value.” Different stakeholders (donor, government, communities) may value different outcomes. For example, a community might prioritize improvements in governance or empowerment that don’t show up in a cost-benefit analyses. Conventional methods rarely allow a nuanced, multi-dimensional view of value that includes social, environmental, and equity considerations alongside financial returns.

The consequences are profound. When funding decisions rely solely on traditional value-for-money metrics, we risk misrepresenting—or entirely missing—the real impact of complex programs. We might inadvertently discourage high-impact interventions just because they don’t fit the mold of simple accounting. This is why a new approach is needed. We must preserve rigor and accountability in how we spend money, but expand our notion of value to capture systemic and long-term benefits.

Emergent Value: A Systems Approach to VfM

To address the inherent limitations of conventional value for money approaches, the Emergent Value framework offers a necessary evolution. This approach moves beyond simplistic input-output calculations to provide a more nuanced and realistic understanding of how investments generate value within dynamic systems. Emergent Value is fundamentally about recognizing that significant development outcomes often arise unpredictably from the interactions within a system, rather than solely from the direct, linear effects of isolated interventions. It builds on principles from systems thinking, adaptive management, behavioral change, and public value to create a framework that is both logically rigorous and pragmatically flexible. It focuses on understanding chains of influence, shifts in actor behavior, the quality of relationships, and the overall health of the system, acknowledging that value itself can be multifaceted and evolve over time.

The Emergent Value approach is built on a few key principles:

- Look at the whole picture, not just isolated parts: Value comes from how all pieces of a system work together, so we examine the entire landscape and understand connections between different elements to see how change in one area affects others. Traditional value for money often focuses narrowly on isolated interventions, missing the bigger picture of how components interact. By seeing the whole picture, we can make better investment decisions that leverage connections between different parts of the system for greater collective impact.

- Different people value different things: We start by asking “valuable to whom, and in what ways?” Value isn’t just economic savings or immediate outcomes – it encompasses social, environmental, and governance gains as well. Emergent Value involves stakeholders in defining what success looks like. We might measure improvements in community trust or environmental resilience alongside traditional metrics. Crucially, we consider equity (who benefits?) and time (short-term wins vs. long-term impact). By capturing a richer picture of value, we ensure that important benefits (like a more resilient local health system) aren’t ignored just because they’re hard to monetize.

- Find the right change-makers: In any system, some players and factors have outsized influence. Rather than treating all inputs equally, we identify the pivotal actors or bottlenecks that, if shifted, can unlock big change. For example, in an education reform, the “leverage point” might be school principals’ leadership quality. We focus interventions on influencing these high-impact points. This also means designing projects to encourage positive relationships and networks among actors – since collaboration can multiply value. In short, we aim for catalytic changes: those initial behavior shifts that can cascade through the system, creating a multiplier effect on value.

- Designing clear pathways from investment to impact: Emergent Value forces us to be very explicit about how an investment will lead to the desired change. We map out “value pathways” – basically, a theory of change that links our resources to activities, to actor behavior changes, and finally to system-level outcomes. This is done using human-centered design thinking, meaning we co-design solutions with the people involved to ensure they fit the context. For each pathway we ask: How will this particular intervention (a policy, a training, a new service) change the ability or motivation of a key actor? And how will that actor’s change influence others in the system? By articulating these pathways, we make the causal logic testable and transparent. It keeps everyone focused on the ultimate outcomes, not just the immediate outputs.

- Try multiple approaches together: Complex problems don’t have one magic bullet, so we use a portfolio approach. This means pursuing a mix of initiatives – some low-risk, some experimental – rather than betting everything on a single solution. In practice, we might implement several coordinated projects (for example, combining technology upgrades with staff training and policy reforms) to address different facets of a problem. We explicitly consider the cost, expected value, and uncertainty of each intervention, aiming for a balanced portfolio that maximizes overall impact. By diversifying approaches, we also foster synergies (one intervention boosting the effectiveness of another) and ensure we’re not “putting all our eggs in one basket.” The portfolio mindset acknowledges that in dynamic systems, a combination of efforts often yields more value together than any one piece could alone.

- Learn and adapt continuously: Unlike static value for money assessments, Emergent Value is dynamic and iterative. We put in place feedback loops to trace the value pathways during implementation. Instead of just measuring direct outputs, we monitor indicators that reflect the health of the overall system (e.g. trust between citizens and government, market activity levels, service usage rates). We also use theory-based evaluation methods (like contribution analysis) to assess whether our interventions are truly contributing to observed changes. Where appropriate, we’ll even attach dollar values to social outcomes (using tools like Social Return on Investment) to compare benefits with costs in a more holistic way. Most importantly, we stay agile: if the data shows an approach isn’t delivering as expected, we adjust course. Regular learning sessions are built in so that the team can refine strategies, reallocate resources, or tweak interventions. This adaptive management ensures we continually maximize value as conditions evolve.

Emergent Value in Practice

The principles of Emergent Value provide a practical framework for designing, managing, and evaluating complex development initiatives across various sectors. The following example illustrates how this approach differs from traditional value for money applications.

Imagine a health system strengthening program, where traditional value for money approaches would focus on cost-effectiveness analysis of specific interventions (like midwife training) with clear metrics of cost per life saved and standardized implementation targets. Applying Emergent Value would incorporate these calculations while also mapping the broader health system, engaging diverse stakeholders to define "value" more comprehensively—for instance, communities might prioritize respectful care and cultural appropriateness, district officials may value system sustainability, and providers might emphasize professional growth opportunities. This approach would identify key relationships as leverage points, such as the supervisory connection between district health officers and facility staff, or the trust relationship between community health workers and mothers that determines care-seeking behaviors. This matters profoundly because these relationships often determine whether investments translate into actual behavior change and sustainable outcomes. When a supervision system breaks down, even perfectly trained health workers may revert to old practices; when community trust erodes, expensive facilities sit empty. By understanding and strengthening these crucial connections, we ensure that each dollar invested reinforces rather than undermines other parts of the system.

In the event of budget cuts, using a traditional approach might lead you to maintain the core strategy while proportionally reducing scope (training fewer midwives or covering fewer districts), while applying Emergent Value might reconfigure resources based on insights about which combinations of interventions yield the greatest systemic impact, perhaps maintaining investment in supervision quality while slightly reducing the number of new midwives trained, recognizing that better-supported providers deliver higher quality care and remain in their posts longer.

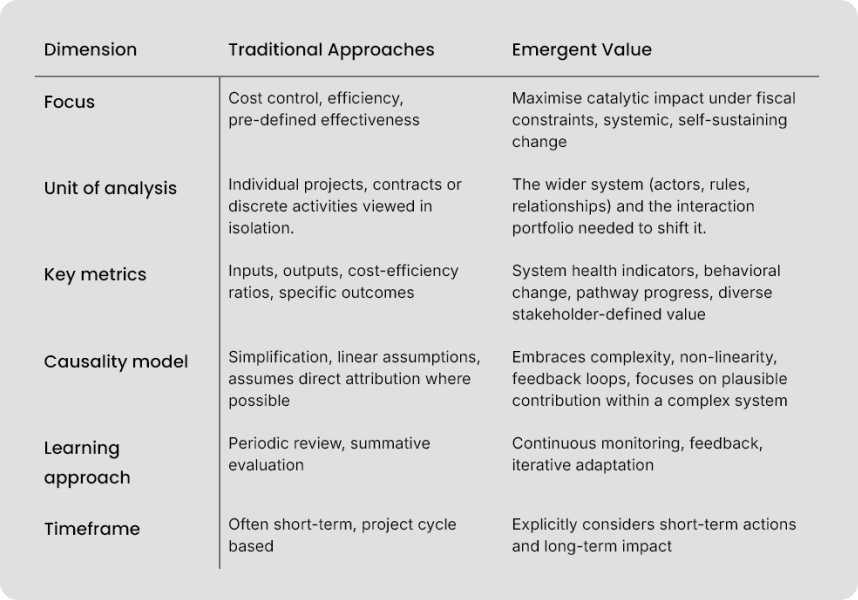

The fundamental differences between traditional value for money approaches and the Emergent Value framework can be summarized across several key dimensions:

Conclusion

In summary, the Emergent Value approach acknowledges that value in complex programs is often emergent – it unfolds over time through interactions. By embracing this complexity rather than ignoring it, we provide a more credible and useful account of value for money. This framework doesn’t abandon rigor – it builds on proven principles from public value theory, behavioral science, and adaptive management – but it applies them in a pragmatic way for real-world projects. The result is a approach to value for money that can guide better decision-making (where to invest for the biggest payoff in a system) and strengthen our narrative about why transformative initiatives are worth funding, even in lean times.